Choosing Composition Over Inheritance: A Practical News Model Design

🌑 Outline

Architect Weaver  was working on a news application that displayed articles in different formats. News could appear in short format or long format. The goal was simple: build models that could hold all these variations without becoming rigid or confusing.

was working on a news application that displayed articles in different formats. News could appear in short format or long format. The goal was simple: build models that could hold all these variations without becoming rigid or confusing.

How can a news model be designed so it grows to support short updates, long reports, and any future format without becoming rigid or confusing?

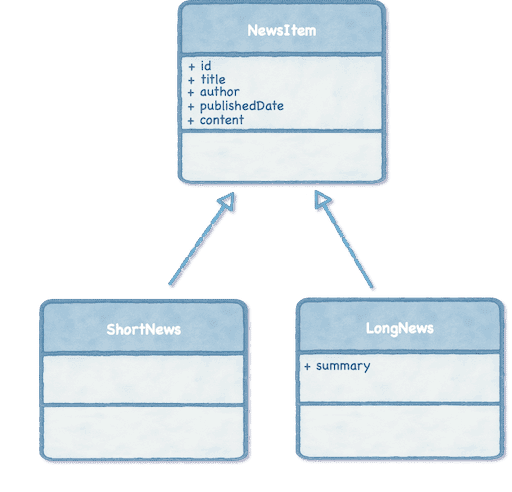

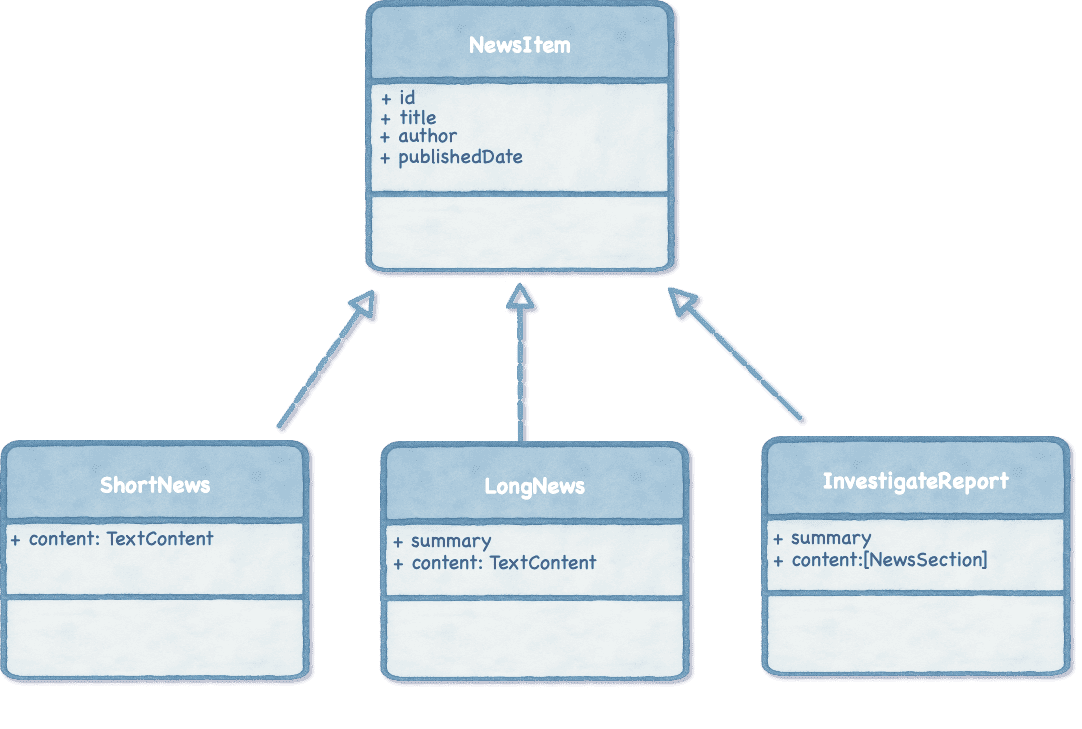

Inheritance is a natural choice for Weaver. It feels simple and familiar: create a base NewsItem and let each format extend it. Even on the UI side, this fits nicely at first. A single base class can represent both formats.

Here, ShortNews doesn’t introduce any new fields, but separating the types early still helped. It allowed Weaver to keep the model ready for future changes—different layouts, special flags, or unique business rules—without complicating the base class.

🌥️ First Signs of Trouble

Shortly after a release, a new requirement arrived. The app needed to support InvestigativeReport, a format that didn’t fit into a single text block and required multiple structured sections.

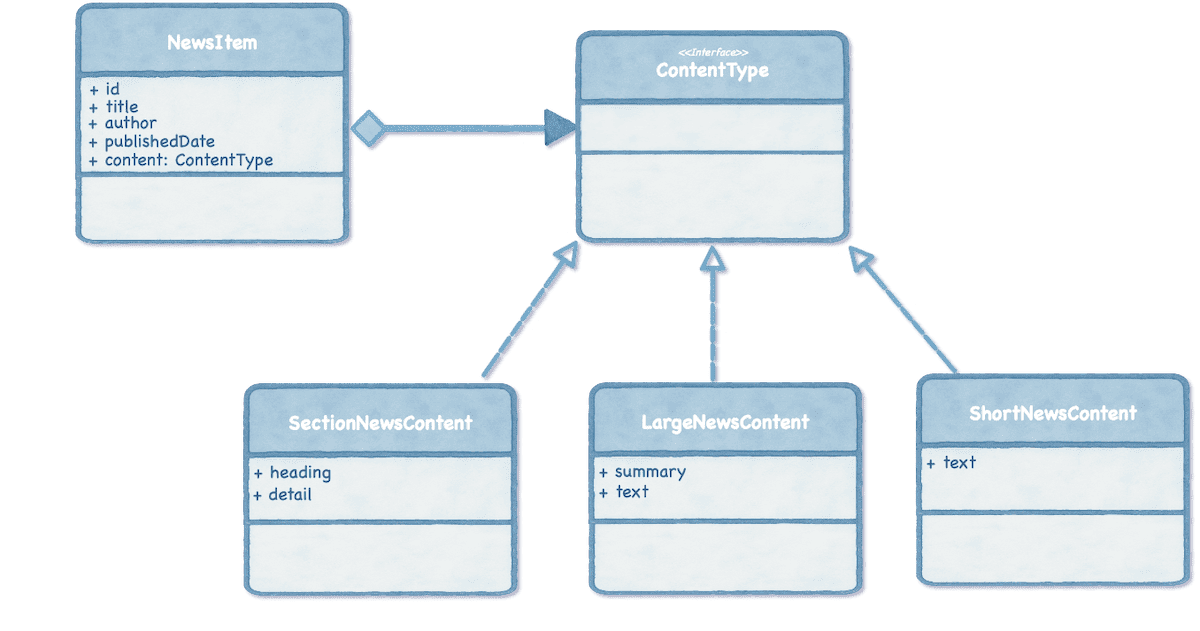

To handle this, Weaver introduced a ContentType interface and replaced the earlier content: String with a polymorphic content: ContentType, hoping this would make the model flexible enough for structured articles.

Each derived class now created the content it needed—ShortNews and LongNews used text-based content, while InvestigativeReport used a section-based one. On the surface, this worked.

But something felt off. The base class no longer understood or constrained its most important property. UI code could no longer make even simple assumptions—whether an article had a single body of text, a summary, or multiple sections—without checking the concrete type first. Instead of defining a clear structure, it had become a passive container that merely held some content without knowing what that content meant.

🌜 Why Inheritance Fails Here

The deeper issue was that the domain itself didn’t fit inheritance. In this case, the article formats had completely different content shapes—some contained plain text, others summaries, and others full sections.

When a parent type cannot enforce anything meaningful about the data it owns, the core idea behind inheritance breaks down. The base class could no longer reason about its content, validate it, or make assumptions about it. At that point, the inheritance hierarchy stopped expressing the domain and became a liability.

A news item naturally splits into two parts:

Metadata — stable information shared by all articles (id, author, publish time, category)

Metadata — stable information shared by all articles (id, author, publish time, category)

Content — the actual body of the article, which varies widely by format

Content — the actual body of the article, which varies widely by format

The metadata has a clear, shared shape and belongs in a single model. The content does not. Each article format carries its own content structure, and that variability is exactly what breaks inheritance.

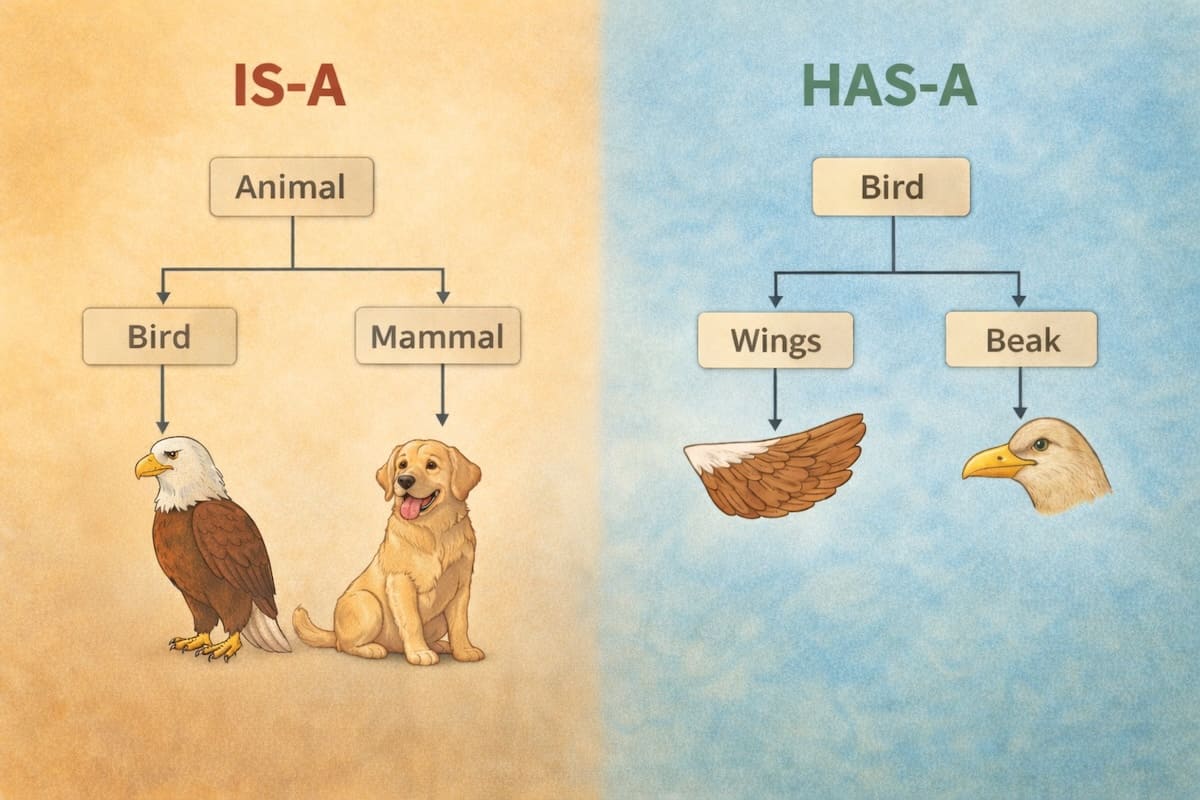

If all variation between types lives inside a single field, the relationship is not truly is-a — it is has-a.

Once the domain stopped offering a shared structure, inheritance no longer fit to model.

🌕 Moving Toward Composition

With inheritance no longer matching the shape of the domain, Weaver shifted focus from what an news item is to what an news item has. Every news item clearly consisted of two parts—metadata and content—but only the metadata was truly shared across formats.

Instead of forcing different content structures into a single hierarchy, the model was reoriented around composition. The base type retained only shared metadata, while content became a separate component that could vary independently for each article format. From this point onward, the design no longer needed to justify why inheritance failed—the structure itself made the decision obvious.

A Simple Adjustment: News Types Hold Their Content

Weaver realized that putting content directly inside NewsItem was breaking the is-a relationship. The base class could not represent the different content shapes used by various news types, so it shouldn’t try to define them. To solve this, he introduced a dedicated content model. Now, each news type has a content object, but the actual content type is chosen independently by each format:

ShortNews → uses simple text content

LongNews → uses text content with an optional summary

InvestigativeReport → uses section-based content

This shift made the structure much clearer. The base class only held the part all articles truly share—the metadata. The content became flexible and expandable without disturbing the main hierarchy.

Adding New Formats Becomes Easier With composition in place, new article formats no longer require changes to the base class or the inheritance tree. They simply introduce a new content type:

PhotoNews → PhotoContent

PhotoNews → PhotoContent

VideoNews → VideoContent

VideoNews → VideoContent

Each article type remains simple, and each content type can evolve independently.

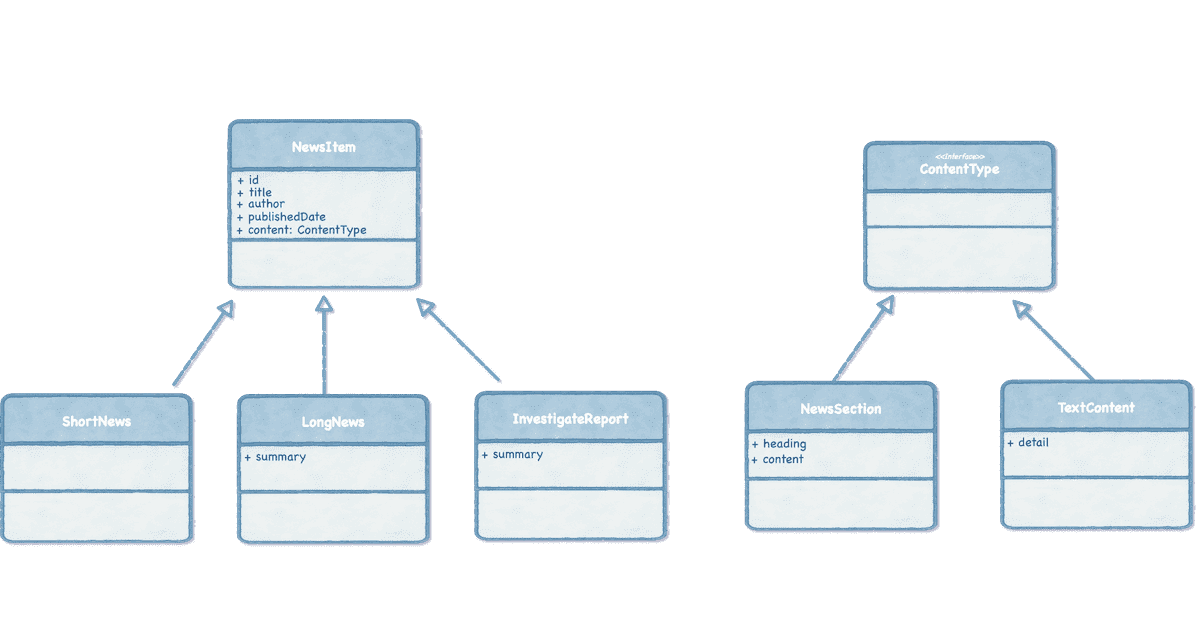

Complete Refactor: A Clean and Extensible Model

After separating content from metadata, the remaining inheritance no longer served a real purpose. The subclasses did not introduce new behavior, rules, or responsibilities—they only existed to hold different kinds of content.

This made Weaver question the entire approach. To think it through, he asked himself a simple question:

Is an InvestigativeReport a NewsItem(Metadata), or does an InvestigativeReport simply have a NewsItem(Metadata)?

At that point, the hierarchy itself became unnecessary. All articles shared the same identity and behavior, and only their content varied. The model was simplified into a single, stable NewsItem that owned its metadata and delegated all variation to composable content types.

At that point the real issue wasn’t that inheritance “broke later.” The truth was much simpler: inheritance was never the right tool from the beginning. Inheritance is meant for situations where types are truly different in behavior or rules—not when they only hold different kinds of content or data.

Inheritance works when:

The objects behave differently

The objects behave differently

The types represent different roles or identities

The types represent different roles or identities

Each subclass adds real logic or rules

Each subclass adds real logic or rules

Inheritance fails when:

The only difference is in the content or fields, not in behavior. This is a common mistake. Many models seem to need inheritance, but once you look closely, all the variation is actually inside one field—just like the NewsItem example.

With this understanding, Weaver completed the final refactor.

In the refactored model, NewsItem becomes a single, stable class that holds only shared metadata. All variations—short updates, long articles, investigative reports, or any future format—are handled by different content types instead of different subclasses. This makes the design cleaner, easier to extend, and avoids the problems that come with inheritance.

🌑 When Inheritance Works Well

Inheritance is still useful when the types are truly different in behavior, not just in data. when each subclass adds its own rules, logic, or behavior, inheritance expresses the domain clearly.

So Weaver tried to create a simple checklist to decide when inheritance actually makes sense:

Inheritance Checklist:

There is a real IS-A relationship:

There is a real IS-A relationship:

The subclass must truly be a more specific kind of the parent (e.g., Player is-a Character, Bird is-a Animal). LongNews does not qualify because it isn’t a new kind of NewsItem — it’s the same NewsItem with different content.

The subclass changes behavior, not just data:

The subclass changes behavior, not just data:

It adds new logic or overrides how things work. LongNews does not introduce any new behavior; it only holds extra fields.

The domain clearly expects separate types:

The domain clearly expects separate types:

The type exists because the domain expects it, not because the data shape changed. For example, an Error can have real subtypes like NetworkError or FileError because they represent different kinds of failures—not just different pieces of data.

“Use inheritance for different behavior. Use composition for different content.”

🌑 Summary

Weaver understood that while inheritance can feel natural at first, it only works when the domain truly has different types with different behavior. eventually realized that the news formats were not real subtypes—they shared the same metadata and differed only in content. That’s why composition turned out to be the better and more flexible choice.

| Use Inheritance When… | Use Composition When… |

|---|---|

| ✔ Types behave differently | ✔ All types share the same behavior |

| ✔ Subclasses add real logic or rules | ✔ Only data or content changes |

| ✔ Domain has true subtypes (Bird, Error, etc.) | ✔ One type has many content formats (like NewsItem) |

Summary – Voice Recording

🧘 Final Thoughts

Architect Weaver  saw that inheritance was never the problem—it simply wasn’t the right tool. The news formats behaved the same and differed only in what they contained, not in what they did.

saw that inheritance was never the problem—it simply wasn’t the right tool. The news formats behaved the same and differed only in what they contained, not in what they did.

Different behavior calls for inheritance. Different content calls for composition.

Recap & Reflection

If two types differ only in their content structure (different fields or formats), what is the most appropriate design approach?

Which design choice best signals that two types are real subtypes in the domain?

You have 10 services that all build and send network requests the same way, except LoginService which needs a custom header. What is the cleaner and more flexible design?

You have a Product model used across the app. A new screen needs extra details like specifications, reviews, and seller info, while the Product’s behavior and identity remain the same. What is the better design choice?

A messaging app supports text messages, image messages, and video messages. All messages are sent, stored, and delivered the same way; only the content differs. What is the cleaner design?

A payment can be made using CreditCard, UPI, or NetBanking. Each payment type follows a different validation and processing flow. What design approach fits best?

An authentication system supports PasswordAuth, OTPAuth, and BiometricAuth. Each method follows a different validation and verification flow. What design approach fits best?

A pricing system supports RegularPrice, DiscountPrice, and SubscriptionPrice. Each pricing type calculates the final amount using different rules. What design approach fits best?

In a Clean MVVM setup, you have BaseFetchNewsUseCase with FetchShortNewsUseCase and FetchLongNewsUseCase as subclasses. All use cases follow the same execution flow and differ only by the news type. What is the better design choice?

Comments powered by Disqus.